Left to right: Kath, Joan, Cousin Paul, Roy Junior., Sheila, Roy Senior., Peg

Now it’s 1932, and April brings--along with FDR for president,

And crocuses and bright gold forsythia

Spilling out beneath the big bay window of the dining room--

A little boy who wears a large black bowl of hair upon his head

Who seems to have just arrived by boat from China.

You call him Tim, after your dear Pa,

And you begin to see how quickly you are filling up this house.

You now have six, and precious little time

To call your own. After dinner, perhaps,

When Agnes gets the children gently bathed,

And just as gently tucked in all their beds,

You sit down in your very own burgundy easy chair

And read the Boston Herald to yourself,

Or sit with Dad beside a crackling fire

And listen to the brand-new president

Explain his New Deal on the radio.

Nineteen thirty-four brings death and life:

Your dear Pa dies, but you give birth to David--number 7.

So here the kids are now, in 1938,

With all but little David lined up left to right,

Roy Junior looking every inch the gent,

Just like his dapper dad,

Then Joan and Peg and Sheila, Mike and grinning Tim.

Now it’s 1932, and April brings--along with FDR for president,

And crocuses and bright gold forsythia

Spilling out beneath the big bay window of the dining room--

A little boy who wears a large black bowl of hair upon his head

Who seems to have just arrived by boat from China.

You call him Tim, after your dear Pa,

And you begin to see how quickly you are filling up this house.

You now have six, and precious little time

To call your own. After dinner, perhaps,

When Agnes gets the children gently bathed,

And just as gently tucked in all their beds,

You sit down in your very own burgundy easy chair

And read the Boston Herald to yourself,

Or sit with Dad beside a crackling fire

And listen to the brand-new president

Explain his New Deal on the radio.

Nineteen thirty-four brings death and life:

Your dear Pa dies, but you give birth to David--number 7.

So here the kids are now, in 1938,

With all but little David lined up left to right,

Roy Junior looking every inch the gent,

Just like his dapper dad,

Then Joan and Peg and Sheila, Mike and grinning Tim.

Fast-forward now, past the fearful hurricane of '38

To that more fearful day in February '39

When you learn that your firstborn son has died.

Who else will ever know what you felt then,

When by your grieving heart there beat two unborn hearts--

The hearts of those you long had known were twins?

You bury little Roy, and Dad entombs his grief so deep inside

He cannot speak of Roy for months to come.

You bury one, with two more on the way.

But how can two or even two times twenty-two

Replace the one you lost?

You never lost him wholly; he lives yet in your heart.

But that dear heart has always made a place for each of us,

And each of ours.

In that great inn of yours there's always room for more--

Like James and Paul, who found in you a second mother

When theirs was gone.

And so we two arrive on April 22.

We play a numbers game on your own birthday,

For April's two times February, and 22 is twice 11.

We two, however, come out one by one:

Tom wriggles out ahead of me;

I linger, dawdling behind.

But nonetheless, before I leave the womb,

I turn out every light

For even then I know that Dad is looking on.

I see now that it's taken near two hundred lines

To bring the twinny boys into the light of day,

And you will want this dawdling boy of yours

To get a wiggle on before you fall asleep.

So forward march--right into World War II.

Not five months after Tom and I are born,

The German army plant their great jackbooted feet

On Polish soil, and thus it all begins.

Do you thank God that none of your five boys

Is old enough to fill a trench?

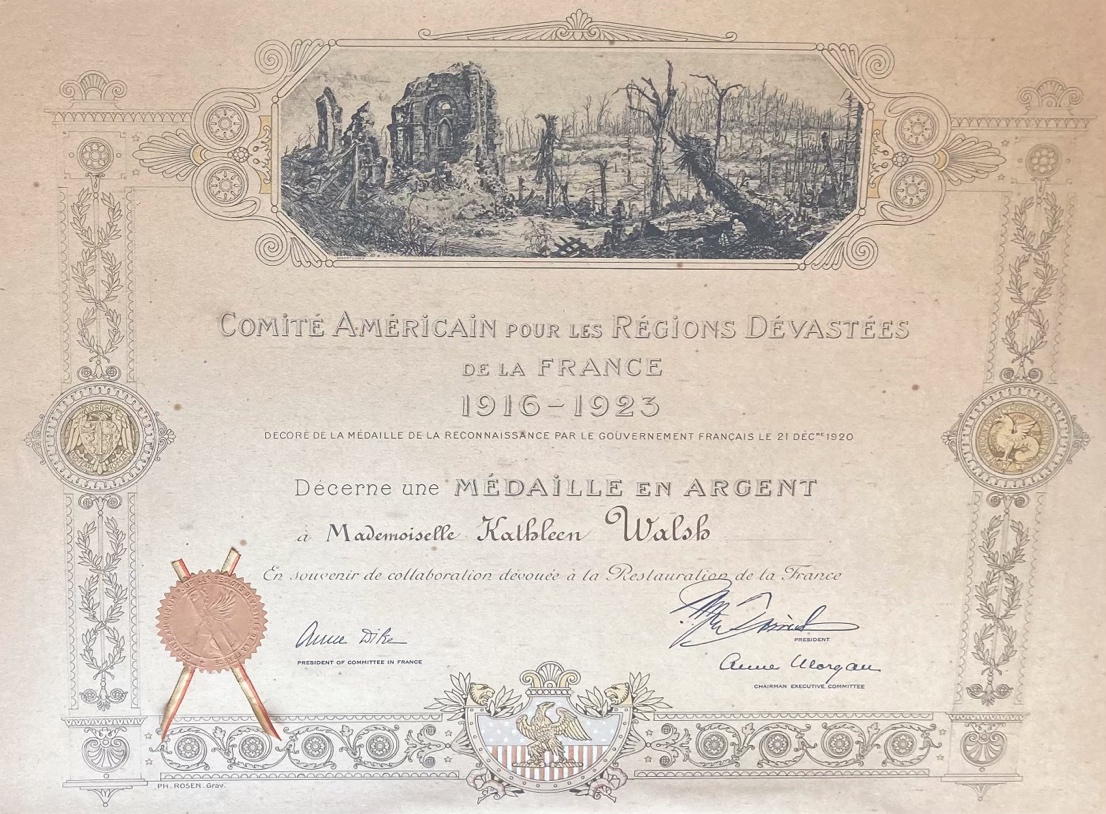

Do you wonder if your students of the waltz

Your onetime raw garçons in old Soissons,

Are marching to a different two-step now,

Or tripping onward to a dance of death?

With eight of us to tend, you have no time to think of them,

And war is just a game we play with sticks and stones,

A game that none of us was asked to play for keeps.

But I remember Austin going off to France in '43 (I think);

I see us crowding round the kitchen entry door to wish him well,

And wondering just why he had to go.

And I remember two young men named Dick and Al,

Who came one night in crisp new uniforms to call for Peg and Joan.

I see them standing now just inside the living room at '46,

Genial, gracious, beaming, grateful for your hospitality,

Looking forward to their night out with the girls,

Perhaps their last before their date with Hitler's guns.

A few months later I came home one day from kindergarten

To find Peg in the sunlit dining room,

Reading a letter that had just arrived from Al

To say that Dick had died in battle.

That was really all I knew of World War II

Until one day I saw a big black headline on the kitchen table:

THE WAR IS OVER.

Those were the first words I can remember reading,

Though long before,

While shells rained down on France and Germany,

You read us tales of Uncle Wiggily, Babar the Elephant, and Winnie,

The one and only Pooh.

Enough of war! Return to the domestic front:

The sunsuits you put on us when the sky was blue,

The birthday suits you let us wear for hailstorms,

The butterfly kisses you made with your fluttering eyebrows

When you tucked us in bed;

The swanboat rides you gave us in the Public Garden,

The roses climbing on the trellis of your garden gate,

The afternoons of skating on Jamaica Pond,

The tinsel we threw down upon the great big Christmas tree,

With presents piled up under it in heaps;

The playroom door on Christmas day, the gateway

To a world of brand-new toys,

Where Tom and I stood first in line each year

With bated breath, and older brothers panting on our necks;

One year Mike nearly trampled us to death

When opening the door we suddenly revealed to him a wrestling mat.

And I remember summer days of swimming out at Ponkapoag,

With cold root beer for lunch and hot dogs from the grille;

And summer weeks at Shinglemere,

"By the sea, by the sea, by the beautiful sea."

That was the song that Tom and I sang in January '45

For the costume party you gave on your twentieth anniversary,

When you wore a great black fitted dress that flared out at your heels

Like the Spanish dancer in Sargent's painting at the Gardner Museum.

What else? You scrubbed our ears and bandaged up our wounds,

You fed a crowd of ten for dinner every night,

And twice that many for high days and holidays;

You bore with all the mayhem in the house,

The spills, the messes, once a midnight waterfall

That filled the living room (my humble contribution to domestic bliss).

You bore it all, and somehow kept the house at '46

A place of light and grace and order,

Banishing dirt, tidying rooms,

Scraping once a month great gobs of ancient dust-encrusted oatmeal

From the backside of the kitchen radiator,

And using your own hairbrush on our backsides

Whenever you perceived we needed it.

In summer '47 you wave goodbye to Mike

As he heads off across the continent

In a 1932 Ford that seemed hardly spry enough

To chug once around the block.

Should you allow a kid of not quite seventeen to drive

Three thousand miles and back in that jalopy

With just a pair of friends to keep him company?

Why not--if he can do it?

You see in him your own lust for adventure,

And something in you cannot bear to hold him back--as if you could!

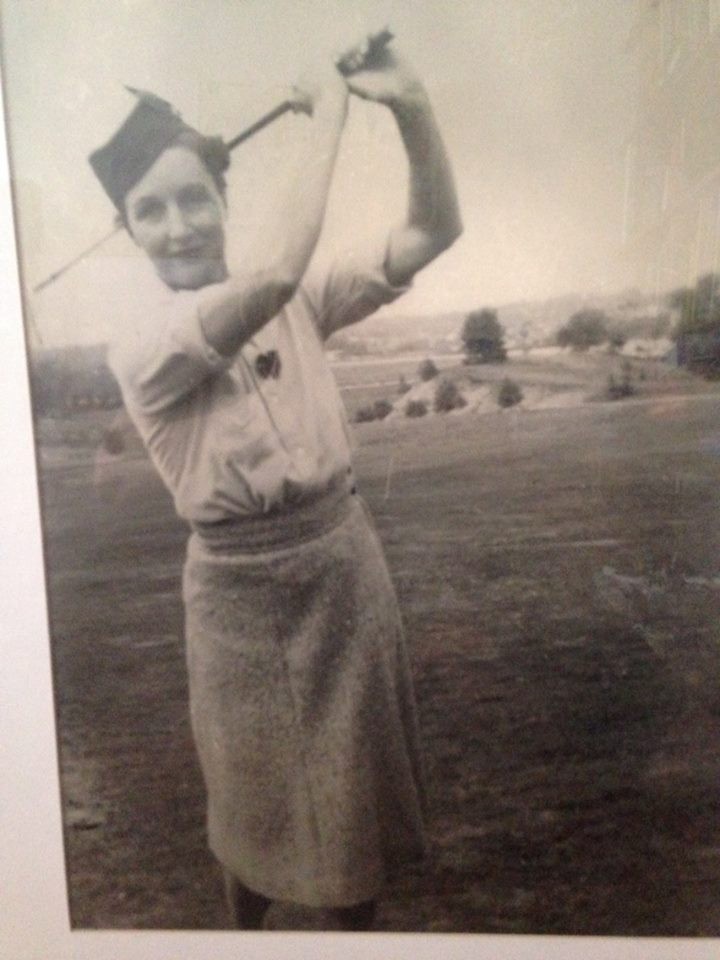

As we kids all grow bigger, you find more time for gardening and golf,

But keep a steady watch on what we do.

In 1950, the magazine called Life proclaims a national disaster:

Juvenile delinquency has come to plague the land.

Children now and then are misbehaving,

A thing unknown to all the ages past.

You take your stand against this dreaded new disease:

To one and all of us you roundly say,

"I will not have juvenile delinquency in my house!"

Your word is law; of course we all obey,

And from that moment on we never stray.

Never? Well, as Dad was fond of saying, hardly ever.

Distinguished doctor's wife, mother of eight,

Queen of endless hospitality,

You nonetheless find time to swing a club

With Dad on Sunday afternoons,

And Saturdays with good old friends like Mary Dalton.

At Wollaston you swing so well

That you become the champion of all the women there eleven times

And twice the Women's Senior Champion of Massachusetts.

Fast-forward now, past the fearful hurricane of '38

To that more fearful day in February '39

When you learn that your firstborn son has died.

Who else will ever know what you felt then,

When by your grieving heart there beat two unborn hearts--

The hearts of those you long had known were twins?

You bury little Roy, and Dad entombs his grief so deep inside

He cannot speak of Roy for months to come.

You bury one, with two more on the way.

But how can two or even two times twenty-two

Replace the one you lost?

You never lost him wholly; he lives yet in your heart.

But that dear heart has always made a place for each of us,

And each of ours.

In that great inn of yours there's always room for more--

Like James and Paul, who found in you a second mother

When theirs was gone.

And so we two arrive on April 22.

We play a numbers game on your own birthday,

For April's two times February, and 22 is twice 11.

We two, however, come out one by one:

Tom wriggles out ahead of me;

I linger, dawdling behind.

But nonetheless, before I leave the womb,

I turn out every light

For even then I know that Dad is looking on.

I see now that it's taken near two hundred lines

To bring the twinny boys into the light of day,

And you will want this dawdling boy of yours

To get a wiggle on before you fall asleep.

So forward march--right into World War II.

Not five months after Tom and I are born,

The German army plant their great jackbooted feet

On Polish soil, and thus it all begins.

Do you thank God that none of your five boys

Is old enough to fill a trench?

Do you wonder if your students of the waltz

Your onetime raw garçons in old Soissons,

Are marching to a different two-step now,

Or tripping onward to a dance of death?

With eight of us to tend, you have no time to think of them,

And war is just a game we play with sticks and stones,

A game that none of us was asked to play for keeps.

But I remember Austin going off to France in '43 (I think);

I see us crowding round the kitchen entry door to wish him well,

And wondering just why he had to go.

And I remember two young men named Dick and Al,

Who came one night in crisp new uniforms to call for Peg and Joan.

I see them standing now just inside the living room at '46,

Genial, gracious, beaming, grateful for your hospitality,

Looking forward to their night out with the girls,

Perhaps their last before their date with Hitler's guns.

A few months later I came home one day from kindergarten

To find Peg in the sunlit dining room,

Reading a letter that had just arrived from Al

To say that Dick had died in battle.

That was really all I knew of World War II

Until one day I saw a big black headline on the kitchen table:

THE WAR IS OVER.

Those were the first words I can remember reading,

Though long before,

While shells rained down on France and Germany,

You read us tales of Uncle Wiggily, Babar the Elephant, and Winnie,

The one and only Pooh.

Enough of war! Return to the domestic front:

The sunsuits you put on us when the sky was blue,

The birthday suits you let us wear for hailstorms,

The butterfly kisses you made with your fluttering eyebrows

When you tucked us in bed;

The swanboat rides you gave us in the Public Garden,

The roses climbing on the trellis of your garden gate,

The afternoons of skating on Jamaica Pond,

The tinsel we threw down upon the great big Christmas tree,

With presents piled up under it in heaps;

The playroom door on Christmas day, the gateway

To a world of brand-new toys,

Where Tom and I stood first in line each year

With bated breath, and older brothers panting on our necks;

One year Mike nearly trampled us to death

When opening the door we suddenly revealed to him a wrestling mat.

And I remember summer days of swimming out at Ponkapoag,

With cold root beer for lunch and hot dogs from the grille;

And summer weeks at Shinglemere,

"By the sea, by the sea, by the beautiful sea."

That was the song that Tom and I sang in January '45

For the costume party you gave on your twentieth anniversary,

When you wore a great black fitted dress that flared out at your heels

Like the Spanish dancer in Sargent's painting at the Gardner Museum.

What else? You scrubbed our ears and bandaged up our wounds,

You fed a crowd of ten for dinner every night,

And twice that many for high days and holidays;

You bore with all the mayhem in the house,

The spills, the messes, once a midnight waterfall

That filled the living room (my humble contribution to domestic bliss).

You bore it all, and somehow kept the house at '46

A place of light and grace and order,

Banishing dirt, tidying rooms,

Scraping once a month great gobs of ancient dust-encrusted oatmeal

From the backside of the kitchen radiator,

And using your own hairbrush on our backsides

Whenever you perceived we needed it.

In summer '47 you wave goodbye to Mike

As he heads off across the continent

In a 1932 Ford that seemed hardly spry enough

To chug once around the block.

Should you allow a kid of not quite seventeen to drive

Three thousand miles and back in that jalopy

With just a pair of friends to keep him company?

Why not--if he can do it?

You see in him your own lust for adventure,

And something in you cannot bear to hold him back--as if you could!

As we kids all grow bigger, you find more time for gardening and golf,

But keep a steady watch on what we do.

In 1950, the magazine called Life proclaims a national disaster:

Juvenile delinquency has come to plague the land.

Children now and then are misbehaving,

A thing unknown to all the ages past.

You take your stand against this dreaded new disease:

To one and all of us you roundly say,

"I will not have juvenile delinquency in my house!"

Your word is law; of course we all obey,

And from that moment on we never stray.

Never? Well, as Dad was fond of saying, hardly ever.

Distinguished doctor's wife, mother of eight,

Queen of endless hospitality,

You nonetheless find time to swing a club

With Dad on Sunday afternoons,

And Saturdays with good old friends like Mary Dalton.

At Wollaston you swing so well

That you become the champion of all the women there eleven times

And twice the Women's Senior Champion of Massachusetts.

You loved the game of golf,

But you made sure you played it by the rules.

One day you played with Boston's Mayor James M. Curley,

A man of something less than perfect probity

Who would not hesitate to bend or even break the law

To get his way.

When your ball landed onetime in the rough,

He picked it up for you and set it on the fairway,

Doubtless thinking he had done a gallant deed.

But little did he know of gallantry.

You put your ball back in the rough and told him firmly,

"Mr. Curley, that's not the way I play this game."

One Saturday you get the yen to ride a motorcycle at the club

For Costume Day. You wear a nylon stocking for a mask,

Dress up like a bandit on the run,

And ride Dave's Harley Davidson around and round the clubhouse

Because you can't remember how to make the damn thing stop.

And I suppose you'd still be chugging round that house

If David hadn't somehow intervened

And found a way to set you on your feet.

At fifty-four you get a special treat:

Your first grandchild, Kathleen, a girl named just for you.

Excitedly you pose one day by the seawall at Shinglemere,

With Mike and Betty and your octogenarian mother

And little Kathleen.

"Four generations!" you say, captured by the camera all at once.

And little Kathy's just the first of what in almost twenty years

Will number thirty-two grandkids in all.

Meantime, as your fledglings start to fly the nest at 46,

You find on Brush Hill Road a gardener's house,

Looking out across a sweeping field to the Neponset River.

You give the stucco walls outside a subtle hue of pink;

You give your special warmth and color to the rooms inside,

With touches here and there of purple, the color you love best.

You have your own Elysian fields of gladioli stretching to the river.

And with Austin's help you plant new gardens on the rolling lawn:

The great green rug where scores of your dear grandchildren will play

At the unbirthday party every year,

When ponies take them round the lower field,

And flying frisbees cleave the golden air.

With all you do for all your children and their children too,

You find the time to be a loving, patient daughter

To the mother who raised you.

You treat her like a queen

When she appears to stay a week or two or three . . . .

You bring her breakfast every day in bed,

And when you've got the great big painted wooden tray

All loaded up with hot oatmeal, and eggs, and fruit,

And toast, and coffee too,

And everything, it seems, that she might want,

You draw the curtains in the music room, where she's been sleeping,

Unveil the emerald lawn that stretches out before her in the sunlit dew,

With all the flowers and the trees in bloom;

You plump her pillows, help her to sit up,

Set the breakast tray upon her lap,

Wish her a hearty good morning, and never flag in your devotion--

Not even when she says to all of this, "Well, where's the marmelade?"

As fifty leads to sixty in your life,

And you make winter quarters down in Florida,

You feel the spirit of your father's artful hand touching your own,

And start to paint in watercolor.

You study line as well as color,

You study shading, symmetry, perspective,

You learn from Emile Gruppé down in Naples,

And from Alva Glidden here at home.

But whatever you may learn from others,

You send your own vitality and grace

Right through the bristles of your brush

To swim and shimmer on the watercolored page.

Before you sign a picture with your famous monogram

We know it's yours because we know your touch.

In January 1960 you go with Dad to Washington, D.C.

To see John F. Kennedy sworn in as president,

And in a long white gown you make your way through snowy drifts

To dance at the Inauguration Ball.

Did you feel you could have danced all night?

What pictures you have made, what wonders you have seen,

Since first you craned your neck and dreamed of flight.

The pictures swim before your eyes:

At Kitty Hawk, the brothers Wright took flight when you were three,

A little girl just gazing at the sky.

With little Roy and Joan a babe in arms, you thrilled to learn

of Lindbergh's solo crossing,

And just a few years into your grandmotherhood,

A man named John Glenn orbited the earth.

Then weeks before your last granddaughter's birth,

Neil Armstrong put his foot upon the moon

And made you catch your breath for what mankind can do.

But what of womankind and of her dreams?

At 95 you make your lifelong dream come true:

You board a basket tethered to a great balloon,

And take your long-planned voyage to the sky.

You dance with clouds and laugh with angels

And blow a kiss to each of your dear Roys.

Then down you come and land right here on earth

But with a look the camera catches for us all:

A look of exaltation and delight

You loved the game of golf,

But you made sure you played it by the rules.

One day you played with Boston's Mayor James M. Curley,

A man of something less than perfect probity

Who would not hesitate to bend or even break the law

To get his way.

When your ball landed onetime in the rough,

He picked it up for you and set it on the fairway,

Doubtless thinking he had done a gallant deed.

But little did he know of gallantry.

You put your ball back in the rough and told him firmly,

"Mr. Curley, that's not the way I play this game."

One Saturday you get the yen to ride a motorcycle at the club

For Costume Day. You wear a nylon stocking for a mask,

Dress up like a bandit on the run,

And ride Dave's Harley Davidson around and round the clubhouse

Because you can't remember how to make the damn thing stop.

And I suppose you'd still be chugging round that house

If David hadn't somehow intervened

And found a way to set you on your feet.

At fifty-four you get a special treat:

Your first grandchild, Kathleen, a girl named just for you.

Excitedly you pose one day by the seawall at Shinglemere,

With Mike and Betty and your octogenarian mother

And little Kathleen.

"Four generations!" you say, captured by the camera all at once.

And little Kathy's just the first of what in almost twenty years

Will number thirty-two grandkids in all.

Meantime, as your fledglings start to fly the nest at 46,

You find on Brush Hill Road a gardener's house,

Looking out across a sweeping field to the Neponset River.

You give the stucco walls outside a subtle hue of pink;

You give your special warmth and color to the rooms inside,

With touches here and there of purple, the color you love best.

You have your own Elysian fields of gladioli stretching to the river.

And with Austin's help you plant new gardens on the rolling lawn:

The great green rug where scores of your dear grandchildren will play

At the unbirthday party every year,

When ponies take them round the lower field,

And flying frisbees cleave the golden air.

With all you do for all your children and their children too,

You find the time to be a loving, patient daughter

To the mother who raised you.

You treat her like a queen

When she appears to stay a week or two or three . . . .

You bring her breakfast every day in bed,

And when you've got the great big painted wooden tray

All loaded up with hot oatmeal, and eggs, and fruit,

And toast, and coffee too,

And everything, it seems, that she might want,

You draw the curtains in the music room, where she's been sleeping,

Unveil the emerald lawn that stretches out before her in the sunlit dew,

With all the flowers and the trees in bloom;

You plump her pillows, help her to sit up,

Set the breakast tray upon her lap,

Wish her a hearty good morning, and never flag in your devotion--

Not even when she says to all of this, "Well, where's the marmelade?"

As fifty leads to sixty in your life,

And you make winter quarters down in Florida,

You feel the spirit of your father's artful hand touching your own,

And start to paint in watercolor.

You study line as well as color,

You study shading, symmetry, perspective,

You learn from Emile Gruppé down in Naples,

And from Alva Glidden here at home.

But whatever you may learn from others,

You send your own vitality and grace

Right through the bristles of your brush

To swim and shimmer on the watercolored page.

Before you sign a picture with your famous monogram

We know it's yours because we know your touch.

In January 1960 you go with Dad to Washington, D.C.

To see John F. Kennedy sworn in as president,

And in a long white gown you make your way through snowy drifts

To dance at the Inauguration Ball.

Did you feel you could have danced all night?

What pictures you have made, what wonders you have seen,

Since first you craned your neck and dreamed of flight.

The pictures swim before your eyes:

At Kitty Hawk, the brothers Wright took flight when you were three,

A little girl just gazing at the sky.

With little Roy and Joan a babe in arms, you thrilled to learn

of Lindbergh's solo crossing,

And just a few years into your grandmotherhood,

A man named John Glenn orbited the earth.

Then weeks before your last granddaughter's birth,

Neil Armstrong put his foot upon the moon

And made you catch your breath for what mankind can do.

But what of womankind and of her dreams?

At 95 you make your lifelong dream come true:

You board a basket tethered to a great balloon,

And take your long-planned voyage to the sky.

You dance with clouds and laugh with angels

And blow a kiss to each of your dear Roys.

Then down you come and land right here on earth

But with a look the camera catches for us all:

A look of exaltation and delight